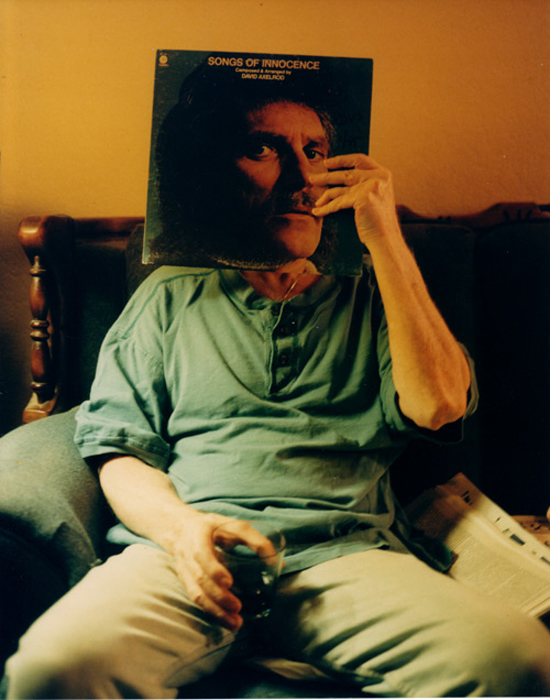

Photo by B Plus, courtesy of Dana Axelrod

On Feb. 5, 2017, composer, arranger and producer David Axelrod, whose work has been sampled by several of the biggest names in hip hop, passed away at the age of 83.

This interview with Linda A. Rapka was originally published in the May 2011 issue of the AFM Local 47 Overture newspaper.

A golden producer in the heyday of Capitol Records, David Axelrod lent his magic to hit jazz, funk and soul records of the 1960s and ’70s. He churned out a succession of gold records and top singles with artists including Lou Rawls, Cannonball Adderley and the Electric Prunes, and his signature sound is a sampling favorite of today’s hip hop artists. His keen eye for spotting unlikely successes garnered him a lasting imprint on some of the most eccentric albums of the era. Sailor-mouthed and charmingly surly, Axelrod minces no words about his improbable highs and cavernous lows during six decades in the industry.

Raised in the tough black neighborhood of South Central, Axelrod started going out to the clubs at 15. “If you were in diapers and you had cash, they would serve you,” he recalled. “We went there because we could get served. But then I started listening to the music.”

Big Joe Turner, Jimmy Witherspoon, Amos Milburn and other prominent black jazz and R&B artists of the Central Avenue scene turned Axelrod on to the world of music. In the late 1950s he spent a stint on the east coast, where he befriended the likes of Charles Mingus, Buddy Collette, Ernie Andrews and Gerald Wiggins. But his love of L.A. soon led him back home, where he found session work drumming for TV and film scores. His shift to producing made waves in jazz circles with his work on hard-bop tenor saxophonist Harold Land’s “The Fox” in 1959.

Known for big beats and deep bass lines, the Axelrod sound was much heavier than typical of that era. “I liked mixing the rhythms like rock with jazz and add classical sounding strings,” he said. “Nobody was doing that. I don’t know why. It seemed like a natural thing to do, I thought.”

He landed at Capitol in 1964 under Alan Livingston, for one simple reason: “That’s where I wanted to be.” Located in Los Angeles, it was the only major outside of New York and Chicago, and he wasn’t about to leave his hometown again. That same year Capitol struck gold with the Beatles, which afforded unorthodox thinkers like Axelrod more leeway to experiment. He did A&R, wrote and produced a succession of gold albums and hit singles including Lou Rawls’ “Dead End Street” and Cannonball Adderley’s “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy!” and helped steer the company in new directions. His unprecedented move to hire black promoters to push Capitol’s black artists paid off big. His idea to sign blond, blue-eyed pin-up actor David McCallum of “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.” fame, despite the fact he had no previous experience and couldn’t sing, landed four hit records. Axelrod was the golden boy.

In 1968 he broke ground blending psychedelic rock with string arrangements on the Electric Prunes’ concept album “Mass in F Minor,” wholly composed, arranged and conducted by Axelrod. Sung in Latin, the album was received as innovative and adventurous and gained heightened popularity when the song “Kyrie Eleison” appeared in the cult film “Easy Rider.”

But the album’s success came back to bite him; it was recorded not for Capitol, but for Reprise. “Livingston had a fit!” Axelrod mused. “After he yelled at me for a while, he said, ‘You’ve got to write an album for us. That’s an order.’ I said, ‘Oh, well OK.’ Like I wasn’t happy about it.”

That year he set to work on his first solo effort. Inspired by the poems and illustrations of English artist William Blake, the end result was a quixotic blend of pop, rock, jazz, theater music, and R&B using a rock orchestra. “Song of Innocence” surprised everyone when it met with widespread critical and popular success. “It turned everything upside-down,” Axelrod said. “Suddenly everyone’s trying to do it. Especially in the U.K.” Another Blake-inspired album, “Songs of Experience,” followed in 1969.

During this time he continued to work with Adderley, Rawls and others including South African singer Letta Mbulu and bandleader David Rose. In 1970, with the exit of Livingston, Axelrod left Capitol. On the verge of making an album putting music to Alan Ginsberg’s celebrated poem “Howl!” tragedy struck when Axelrod’s 17-year-old son died. “Ginsberg was so hip. We talked about it,” he said. “He told me certain things that were gonna happen because of my son dying. And he was right. They did.” A few short years later, close friend and collaborator Cannonball Adderley died of a stroke. Axelrod’s work slowed, and three solo albums he recorded in the 1980s went unreleased.

In the early 1990s his music found renewed interest by the hip hop generation. His beats are sampled all over tracks by Dr. Dre, the Wu Tang Clan, Lauryn Hill, DJ Shadow, De La Soul, Sublime, Lil’ Wayne and others. This surprised no one more than Axelrod himself. “I’m reading that I’m one of the most sampled artists, and I’m going, ‘Where the hell is the money?’” Though everyone was using his music, almost no one was paying royalties. He and his attorney are hoping to stave off drawn-out lawsuits by settling out of court.

In 1993 he released his first album in over a decade, “Requiem: Holocaust,” and several compilations of his earlier work were also released. In 2001 he released the self-titled album “David Axelrod” on British DJ James LaVelle’s label Mo’Wax, which features new arrangements of 30-year-old rhythm tracks originally recorded for an unrealized third Electric Prunes album. For the first time in his career, in 2004 he headlined a sold-out concert at London’s Royal Festival Hall.

Axelrod continues to write music for an hour or two each day, but not for any particular project. “It doesn’t need to be anything that’s gonna be concrete or done,” he said. “It’s just writing. It’s just to keep your mind active physically. You’ve got to stay in shape.”

Now 80, Axelrod has no plans to stop making music anytime soon. “What the hell else am I gonna do?”